By Stephen B. Young

Global Executive Director of the Caux Round Table for Moral Capitalism

Pegasus: A Newsletter for the Caux Round Table for Moral Capitalism

September 2025 (Volume XVI, Issue IX)

John Andrew Morrow has produced a finely researched account of a little-known dimension of Islamic history: how the Prophet Muhammad, acting as God’s representative, went out of his way to respect and protect Christians.

The Prophet extended his “wing of mercy” not only to Christians, but also to other religious communities. If this spirit of equity and compassion were recovered by Muslims today and reciprocated, in turn, by Christians and Jews, three outcomes might follow: (1) the war in Gaza could be brought to an honorable conclusion for both sides; (2) the status of Palestinians in relation to the Jews of Israel could be secured with dignity; and (3) communal tensions, including episodes of inter-group violence in Lebanon and Syria, could be effectively overcome.

Morrow deserves the gratitude of all who seek to understand the covenants the Prophet Muhammad issued during his ministry to respect and protect Christian and Jewish communities. His 2013 work, The Covenants of the Prophet Muhammad with the Christians of the World, was groundbreaking in bringing these documents to broad public attention and made an energizing contribution to our collective understanding of them. In his new book, he presents seven case studies related to the covenants, tracing their provenance and their transmission through the centuries.

What general conclusions may be drawn from these historical studies?

First, there was an era Morrow calls “Prophetic Islam,” which prevailed during the Prophet’s lifetime and continued for several decades after his death. Following the assassination of ʿAlī in 661 CE, the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, the caliphate passed to the Umayyads and, after their fall in 750 CE, to the ʿAbbasids. As Islam grew increasingly politicized and the Sunni schools of law took shape, the covenants personally granted by the Prophet were gradually set aside. By about 850 CE, within Sunni circles, a new text, known as the Pact of Umar, rose to prominence. This document effectively displaced the Prophet’s own promises, providing justification to treat Christians and Jews not as respected partners, but as subordinate and marginalized subjects under the authority of the state and its official theology.

Secondly, drawing on the insights of the German sociologist Max Weber, this shift can be understood as the “routinization of charisma,” the replacement of Prophetic Islam with a rule-based, more doctrinal and intolerant order. Over time, the Prophet’s personal charisma was supplanted by institutions governed by dogma, rules, regulations, conformity of thought and behavior and bureaucratic authority. Weber observed a similar process in Christianity, where the life of a charismatic founder gave way to the institutionalization of the faith under Roman imperial power, exemplified by Constantine and the Council of Nicaea held exactly 1,700 years ago.

The institutionalization of charisma leaves the community of believers bound by sanctioned doctrines and practices, with an installed leadership determining the “right” path for all. The question Morrow presses upon us is whether Prophetic Islam can, in any meaningful sense, be recovered. In that regard, the Qur’an repeatedly warns against attributing “partners” to God, affirming that He has no equals. Creating a partner of God in our minds is committing a sin, shirk. The Qur’an also states explicitly that God does not love the arrogant or the vainglorious (4:36; 31:18). Pride and self-righteousness can thus become a pathway to shirk. To construct a “partner” for God in human imagination is, in effect, to elevate human reasoning and conceit to the status of divine guidance.

Given these injunctions to restrain the impulse to rival God in vainglory, one may ask to what extent the routinization of charisma, through the application of human reasoning, risks leading to shirk by presuming to “improve” upon ancient realities. Even if Islamic scholars acted with noble intentions, the norms, rules, structures and practices that arose from institutionalized religiosity may not have always fully reflected the will of God as revealed in the original charismatic grace that inspired the religion.

Thirdly, recovering today the words of the Prophet Muhammad, his promises and his pledges, might permit a credible return to Prophetic Islam. Understood humbly within a hermeneutic of mercy and compassion, as embodied in the God of the Qur’an, the Prophet’s covenants provide a touch of earthly charisma that reaches us directly from him. A precedent for such renewal exists in the Reformation, when Martin Luther turned to scripture itself as a greater source of Christ’s grace than the institutional liturgies and writings of the Roman Catholic Church. Luther’s mandate of sola scriptura (“only scripture”) rejected the need for priestly intermediaries between believers and God. By translating the Bible into vernacular German and ensuring its wide distribution, he gave his compatriots direct access to this charismatic grace.

The case in Islam may be different, but if the covenants can be reclaimed as authoritative sources alongside the Qur’an, then the treatment of non-Muslims would be brought into alignment with the Prophet’s vision and thus with Prophetic Islam. Morrow’s case studies illustrate this point.

He first examines the fidelity of the Prophet’s covenants to the revelations of the Qur’an, showing that they stand in harmony, rather than opposition. His method is to juxtapose sentences from the Covenant with the Christians of Najran alongside parallel passages from the Qur’an.

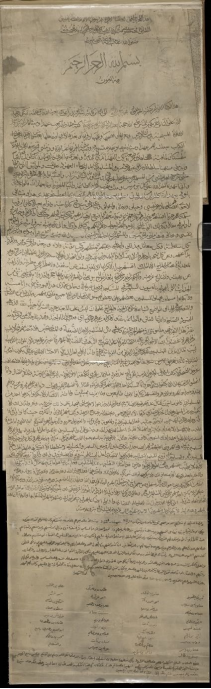

He then provides historical evidence pointing to an actual meeting between the Prophet and the Christian monks of St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai. Surviving copies of a covenant with the monks correspond to this event, giving credibility to its historicity. Morrow even explores the symbolic role of eagles in Muslim and Arabic tradition to underscore the plausibility of their association with

the Prophet.

Fourth, he traces the publication history of Gabriel Sionita’s 1630 Arabic-Latin edition of the Covenant of the Prophet with the Christians of the World. He weighs the question of whether Sionita’s text was genuinely rooted in the Prophet’s covenant or whether it may have been a later forgery, noting Sionita’s participation in a Christian network that promoted moderation and tolerance between Muslims and Christians. Morrow further details the provenance of various recensions, including one held in the Cambridge University Library.

Fifth, he considers a copy of a covenant attributed to the Prophet discovered in 2017 at the Mar Behnam Monastery in Iraq. Written in Syriac script in 1934, it was likely produced by Assyrian Christians during a time of persecution. Although late, it appears to be a faithful reproduction of the Covenant with the Monks of Sinai. Morrow concludes that “the moral and ethical Muslims of our time, along with their Christian friends and allies, are doing precisely what Muslims and Christians have done in the past: uphold the perennial principles of the covenants of the Prophet for the protection of human life and dignity.”

Sixth, he explores visual depictions of the Prophet making covenants with Christians, including those preserved in Rashid al-Din Hamadani’s Compendium of Chronicles (1247-1318). He also examines documents stamped or painted with an impression of the Prophet’s right palm, signifying authenticity and official recognition.

Seventh, he reviews two divergent accounts of the Christians of Najran’s meeting with the Prophet: one respectful and inclusive, the other hostile and dismissive. For Morrow, the key point is that both traditions attest to the fact of the meeting, a detail corroborated by a Qur’anic verse. He further argues that the respectful relationship between the Prophet and the Christians of Najran best reflects Prophetic Islam.

Eighth, he asks whether the Prophet’s covenants were ever annulled after his death. He highlights a “Covenant of Protection” attributed to the jurist al-Shafi‘i (767-820 CE), the founder of the Shafi‘i school of law. Though not an authentic covenant issued by the Prophet himself, this text appears to have been the forerunner to the Pact of ‘Umar. It imposes restrictions on Christians, requiring them to live under Muslim rule and submit to Islamic law, with Morrow describing its tone as “stern, threatening and intimidating,” embodying a rigid and intolerant interpretation of Islam. For him, this represents not only the routinization of the Prophet’s charisma, but also a distortion of Prophetic Islam.

The lasting impression we get from Morrow’s book is that the covenants are in harmony with the Qur’an and supported by a solid historical tradition and manuscript record, including their recognition by rulers and Muslim judges. The “Covenant of Protection” drawn by al-Shafi‘i is particularly revealing, since it shows that the memory of the covenants persisted and compelled Muslim rulers to adapt them to their circumstances. These covenants were known in history, resurfaced across generations and despite neglect or dismissal, they never disappeared. Overall, these documents cannot be ignored in recovering Prophetic Islam today. Morrow’s work provides a compelling case for their reassessment and for their relevance in the present day.